Prostate Cancer

Prostate cancer is the most common cancer in men in the UK

In the UK, about 1 in 8 men will get prostate cancer at some point in their lives. Older men, men with a family history of prostate cancer and black men are more at risk. If you are worried about your risk, or are experiencing any symptoms, go and see your GP. They can talk to you about your risk, and about the tests that are used to diagnose prostate cancer.

Prostate cancer can develop when cells in your prostate start to grow in an uncontrolled way. Prostate cancer often grows slowly and may never cause any problems. But some prostate cancer grows quickly and has a high risk of spreading. This is more likely to cause problems and needs treatment to stop it spreading.

What is the prostate?

The prostate is a gland. Only men have a prostate. The prostate is usually the size and shape of a walnut. It sits underneath the bladder and surrounds the urethra, which is the tube men urinate (pee) and ejaculate through. The prostate’s main job is to help make semen – the fluid that carries sperm.

Does prostate cancer have any symptoms?

Most men with early prostate cancer don’t have any symptoms. So, even if you don’t have symptoms, if you’re a black man over 45, speak to your GP about your risk of prostate cancer.

Some men with prostate cancer may have difficulty urinating. Men with prostate cancer that’s spread to other parts of the body might have pain in the back, hips or pelvis, problems getting or keeping an erection, blood in the urine, or unexplained weight loss.

These symptoms are usually caused by other things that aren’t prostate cancer. For example, if you notice any changes when you urinate or have trouble controlling your bladder, this could be a sign of an enlarged prostate or prostatitis. But it’s still a good idea to talk to your GP so they can find out what’s causing them.

Age

Prostate cancer mainly affects men over 50, and your risk increases with age. The average age for men to be diagnosed with prostate cancer is between 65 and 69 years. If you are under 50, your risk of getting prostate cancer is very low. Men under 50 can get it, but it isn’t common.

If you're over 50 and you're worried about your risk of prostate cancer, you might want to ask your GP about tests for prostate cancer. If you're over 45 but have a higher risk of prostate cancer – because you have a family history of it or you're a black man – you might want to talk to your GP too.

Family history

You are two and a half times more likely to get prostate cancer if your father or brother has had it, compared to a man who has no relatives with prostate cancer.

Your chance of getting prostate cancer may be greater if your father or brother was under 60 when he was diagnosed, or if you have more than one close relative with prostate cancer.

Your risk of getting prostate cancer is higher if your mother or sister has had breast cancer, particularly if they were diagnosed under the age of 60 and had faults in genes called BRCA1 or BRCA2.

If you have relatives with prostate cancer or breast cancer and are worried about your risk, speak to your GP. Although your risk of prostate cancer may be higher, it doesn’t mean you will get it.

Black men

Black men are more likely to get prostate cancer than other men. We don’t know why, but it might be linked to genes. In the UK, about 1 in 4 black men will get prostate cancer at some point in their lives.

If you're a black man and you're over 45, speak to your GP about your risk of prostate cancer. You can also contact our Specialist Nurses.

The PSA test

The PSA test is a blood test that can help diagnose prostate problems, including prostate cancer.

Here we explain who can have a PSA test, what will happen if you have a test, and what your PSA results might mean.

There are advantages and disadvantages to having a PSA test. You’ll need to talk to your GP or practice nurse about these before deciding whether to have a test.

We know that some men have trouble getting a PSA test. You can read more about what to do if this happens.

What is the PSA test?

The PSA test is a blood test that measures the amount of prostate specific antigen (PSA) in your blood. PSA is

a protein produced by normal cells in the prostate and also by prostate cancer cells. It’s normal to have a small amount of PSA in your blood, and the amount rises slightly as you get older and your prostate gets bigger. A raised PSA level may suggest you have a problem with your prostate, but not necessarily cancer.

You can have a PSA test at your GP surgery. You will need to discuss it with your GP first. At some GP surgeries you can discuss the test with a practice nurse, and they can do a test if you decide you want one.

Who can have a PSA test?

You have the right to a prostate specific antigen (PSA) test if you’re over 50 and you’ve thought carefully about the advantages and disadvantages. If you’re over 45 and have a higher risk of prostate cancer, for example if you’re black or you have a family history of it, you might want to talk to your GP about having a PSA test.

It’s important to think about whether the PSA test is right for you before you decide whether or not to have one. There are a number of things you might want to think about.

Your GP or practice nurse may not recommend the PSA test if you don’t have any symptoms, and you have other serious health problems that mean you might not be fit enough for treatment for prostate cancer, or if treatment for prostate cancer wouldn’t help you to live longer. But if you have symptoms of a possible prostate problem, your GP may arrange for you to see a specialist at the hospital.

Some men are offered a PSA test as part of a general check-up. You should still think about the advantages and disadvantages of the test and whether it is right for you before agreeing to have one.

What if my doctor doesn’t want to do a PSA test?

We know that some men having trouble getting a PSA test. There are a number of things you can do if you can’t get a PSA test.

What can the PSA test tell me?

A raised PSA level can be a sign of a problem with your prostate. This could be: • an enlarged prostate

• prostatitis

• prostate cancer.

Other things can also cause men’s PSA levels to rise. If you have a raised PSA level, your GP might do other tests to find out what’s causing it, or they may refer you to see a specialist at the hospital.

The PSA test and prostate cancer

A raised PSA level can be a sign of prostate cancer. But many men with raised PSA levels don’t have prostate cancer. And some men with a normal PSA level do have prostate cancer.

You may be more likely to get prostate cancer if: • you are aged 50 or over, or

• your father or brother has had it, or

• you are black.

To decide whether you need to see a specialist, your GP will look at more than just your PSA level. They will also look at your risk of prostate cancer and whether you’ve had a prostate biopsy in the past. They may also do a digital rectal examination (DRE) to check if your prostate feels normal.

Having a PSA test

You can have a PSA test at your GP surgery. Your GP or practice nurse might talk to you about having a PSA test if you have symptoms such as problems urinating, if you’re worried about prostate problems, or if you’re at higher risk of getting prostate cancer.

Your GP or practice nurse should talk to you about the advantages and disadvantages of the PSA test before you decide to have one. They will also discuss your own risk of getting prostate cancer, and ask about any symptoms you might have.

Your GP or practice nurse will also talk to you about your general health and any other health problems. They might recommend not having a PSA test if you don’t have any symptoms and you have other serious health problems that mean you might not be fit enough for treatment for prostate cancer, or if treatment for prostate cancer wouldn’t help you to live longer.

If you decide you want a PSA test, your GP or practice nurse will take a sample of your blood and send it to a laboratory to be tested. The amount of PSA in your blood is measured in nanograms (a billionth of a gram) per millilitre of blood (ng/ml).

Your GP may also do a digital rectal examination (DRE), also known as a physical prostate exam, and a urine test to rule out a urine infection.

What could affect my PSA level?

Prostate specific antigen (PSA) is produced by healthy cells in the prostate, so it’s normal to have a small amount of PSA in your blood. The amount rises as you get older and your prostate gets bigger. Prostate problems, such as an enlarged prostate or prostatitis, can cause your PSA level to rise – but lots of other things can affect your PSA level too.

- A urine infection – You may have a test for a urine infection as this can raise your PSA level. If you have an infection, you’ll be given treatment for this. You’ll need to wait until the infection has gone – around six weeks – before you have a PSA test.

- Vigorous exercise – You might be asked not to do any vigorous exercise, especially cycling, in the 48 hours before a PSA test.

- Ejaculation – You may be asked to avoid any sexual activity that leads to ejaculation in the 48 hours before a PSA test.

- Anal sex and prostate stimulation – Receiving anal sex might raise your PSA level for a while. Having your prostate stimulated during sex might also raise your PSA level. It might be worth avoiding this for a week before a PSA test.

- Digital rectal examination (DRE) – Having a DRE just before a PSA test might raise your PSA level a small amount. Your doctor might avoid testing your PSA for a week if you’ve just had a DRE.

- Prostate biopsy – If you’ve had a biopsy in the six weeks before a PSA test, this could raise your PSA level.

- Medicines – Let your GP or practice nurse know if you’re taking any prescription or over-the-counter medicines, as some can affect men’s PSA levels.

What will the test results tell me?

- Lots of things can affect your PSA level, so a PSA test alone can’t usually tell you if you have prostate cancer. Your GP will look at the following things to decide whether you need to see a specialist at the hospital:

your PSA level - the results of a DRE

- whether you are at higher risk of prostate cancer • any other health problems or things that may have affected your PSA level

- whether you’ve had any tests for prostate cancer before.

If your doctor thinks your PSA level is higher than it should be for your own situation, they might decide you need to see a specialist at the hospital. For example, they might make an appointment for you to see a specialist if your PSA level is 3 ng/ml or higher. But this is just a guide and slightly higher levels may be normal in older men.

Your GP might decide you don’t need to see a specialist if there are other reasons why your PSA level is raised. In this case, they might suggest having another PSA test in the future to see if your PSA level changes. Your GP might decide to refer you to a specialist if your PSA level is lower than 3 ng/ml but you have a higher risk of prostate cancer for other reasons, such as your family history.

Your GP should discuss all of this with you to help you decide what to do next.

Advantages and disadvantages of the PSA test

It’s important to think through the advantages and disadvantages of the PSA test. Having a PSA test is a personal decision – what might be important to one man may not be to another.

Advantages

- It can help pick up prostate cancer before you have any symptoms.

- It may help to pick up a fast-growing cancer at an early stage when treatment may stop the cancer spreading and causing problems.

- Having regular PSA tests could be helpful for men who are more at risk of prostate cancer. This can help spot any changes in your PSA level, which might be a sign of prostate cancer.

Disadvantages

- You might have a raised PSA level, even if you don’t have prostate cancer. Many men with a raised PSA level don’t have prostate cancer.

- The PSA test can miss prostate cancer. 1 in 7 men (15 per cent) with a normal PSA level may have prostate cancer, and 1 in 50 men (two per cent) with a normal PSA may have a fast-growing prostate cancer.

- If your PSA level is raised you may need more tests, including a biopsy. The biopsy can cause side effects, such as pain, infection and blood in the urine and semen.

- You might be diagnosed with a slow-growing prostate cancer which would never have caused you any problems or shortened your life. But being diagnosed with cancer could make you worry, and you might decide to have treatment that you didn’t need.

- Treatments for prostate cancer have side effects that can affect your daily life, including urinary, bowel, and erection problems.

Should I have a PSA test?

It can be difficult to decide whether or not to have a PSA test. Before you decide, try asking yourself the following questions, or discuss them with your GP or practice nurse.

- Am I at higher risk of prostate cancer?

- If my PSA level was normal, would this reassure me? • If my PSA level was raised, what would I do?

- If I was diagnosed with slow-growing prostate cancer that might never cause any problems, would I want treatment that could cause side effects?

It might help to talk this over with your partner, family or friends. If you want to discuss the test, call our Specialist Nurses. They can help you understand your own risk of prostate cancer and talk you through the advantages and disadvantages of the test.

Regular PSA tests

After some men have had their first PSA test they might want to have regular tests every few years, particularly if they are at higher risk of prostate cancer. This might be a good way to spot any changes in your PSA level that might suggest prostate cancer.

Having a baseline PSA test

A baseline prostate specific antigen (PSA) test involves having a PSA test while your risk of getting prostate cancer is still low – for example when you are in your 40s. The aim of a baseline PSA test is not to help diagnose prostate cancer, but to help work out your risk of getting prostate cancer in the future.

There is some research suggesting that your PSA level in your 40s could be used to predict how likely you are to get prostate cancer, or fast-growing (aggressive) prostate cancer, in the future. If a man’s PSA level in his 40s is slightly higher than most men the same age, he might have a higher risk of getting prostate cancer in the future.

If the test suggests you’re at higher risk, you and your doctor may decide to do regular PSA tests. This might be a good way to spot any changes in your PSA level that might suggest prostate cancer.

However, we don’t yet know exactly what PSA level in your 40s would show an increased risk of prostate cancer, or how often you should have more tests. Because of this, baseline testing isn’t very common in the UK. For more information about baseline testing, speak to your GP.

Worried about going to the GP?

If you’re worried about your risk of prostate cancer or have symptoms, you should speak to your GP.

It’s natural to feel worried or embarrassed about going to the doctor or having tests. But don’t let that stop you going to your GP. Remember, the tests give your GP the best idea about whether you have a problem that needs treating.

If you’re not sure about what to say to your GP, print and fill out this form and show it to them. This will help you have the conversation.

What if my GP won’t give me a PSA test?

You have the right to a PSA test if you’re over 50 and you’ve talked through the advantages and disadvantages with your GP or practice nurse. If you’ve talked about it with your GP or practice nurse, and decided that you want to have one, they should give you a PSA test. But we know that some men have trouble getting the test. There are things you can do if your GP or practice nurse won’t give you a test.

Explain that you are entitled to a PSA test under the NHS Prostate Cancer Risk Management Programme. It might help to take a print out of this webpage along with you. You might also like to print and show them a copy of our information for GPs.

- If they still say no, try speaking to another GP or practice nurse. • If they also say no, speak to the practice manager at your GP surgery.

- Your GP surgery should have information about its complaints procedure. You can follow this procedure, or write to the GP or practice manager explaining your complaint.

If you still have trouble getting a PSA test, you could make a complaint through the NHS complaints procedure. • If you live in England, you can complain to NHS England. The NHS website has more information. - If you live in Scotland, you can make a complaint to your local health board. Get more information from NHS National Services Scotland.

- If you live in Wales, you can make a complaint to your local health board. Health in Wales has more information.

- If you live in Northern Ireland, you can make a complaint to the Health and Social Care board. Get more information from nidirect.

Make sure you include the following information in your complaint: • your name • your contact details – such as your home address, telephone number or email address - a clear description of your complaint – including what happened, where and when

• details of any relevant conversations, letters or emails you’ve had.

You can get advice and support about making a complaint from your local Citizens Advice Bureau.

Questions to ask your doctor or nurse

- Am I at risk of prostate cancer?

- What are the advantages and disadvantages of having a PSA test?

- Will I need a DRE?

- How long will I have to wait for my PSA test results?

- If I have a PSA test and the result is normal, will I need to have regular PSA tests in the future?

- If I have a PSA test and my PSA is raised, what will happen?

- Should I have regular PSA tests?

Digital rectal examination (DRE)

A digital rectal examination (or exam) is used to see if you might have a prostate problem or prostate cancer. It involves your doctor or nurse feeling your prostate through the wall of the back passage (rectum).

What does a DRE involve?

You might have a DRE at your GP surgery or at the hospital.

The doctor or nurse will ask you to lie on your side on an examination table, with your knees brought up towards your chest. They will slide a finger gently into your back passage. They’ll wear gloves and put some gel on their finger to make it more comfortable.

You may find the DRE slightly uncomfortable or embarrassing, but the test isn’t usually painful and it doesn’t take long.

Worried about having a DRE?

It’s natural to feel worried or embarrassed about having tests, but some men find the idea of having a DRE upsetting. For example, if you’ve been sexually abused as a child or an adult, you might feel very upset about having this test. There’s no right or wrong way to feel about this, and it is your choice whether or not you have tests for prostate cancer.

It might be helpful to talk to a counsellor about your experience, thoughts and fears. Or you could contact a charity for people who’ve been sexually abused, such as the National Association for People Abused in Childhood (NAPAC)or SurvivorsUK.

If you do decide to have a DRE, explain your situation to your doctor as they can talk through the test with you and help to reassure you.

What do the DRE results mean?

A digital rectal examination (DRE) is a test used to see if you might have a prostate problem or prostate cancer. Your prostate may feel: • normal – a normal size for your age with a smooth surface • larger than expected for your age – this could be a sign of an enlarged prostate

- hard or lumpy – this could be a sign of prostate cancer.

The DRE is not a completely accurate test. Your doctor or nurse can’t feel the whole prostate. And a man with prostate cancer might have a prostate that feels normal.

What happens next?

Your GP will talk to you about all your test results and what they might mean. If they think you may have a prostate problem, they may be able to talk you through the possible treatment options with you. Or if your GP thinks you may need further tests, they may make an appointment for you to see a specialist at the hospital. If they think you could have prostate cancer, you will usually see the specialist within two weeks. They might recommend that you have a prostate biopsy or a scan.

MRI scan

An MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) scan uses magnets to create a detailed picture of your prostate and the surrounding tissues.

In many hospitals you may have a special type of MRI scan, called a multi-parametric MRI (mpMRI) scan, before having a biopsy. This can help your doctor see if there is any cancer inside your prostate, and how quickly any cancer is likely to grow.

In other hospitals, you may have a biopsy first, followed by an MRI scan to see if any cancer found inside the prostate has spread.

Not all hospitals are able to do mpMRI scans before biopsy, but your doctor may be able to refer you to one that does.

An MRI scan may not be possible if you have a pacemaker or other metal inside your body. What are the advantages and disadvantages of having an MRI scan before a biopsy?

Advantages

- It can give your doctor information about whether there is cancer inside your prostate, and how quickly any cancer is likely to grow.

- It’s less likely than a biopsy to pick up a slow-growing cancer that probably wouldn’t cause any problems in your lifetime.

- It can help your doctor decide if you need a biopsy – if there’s nothing unusual on the scans, this means you’re unlikely to have prostate cancer that needs to be treated. You may be able to avoid having a biopsy, and its possible side effects.

- If you do need a biopsy, your doctor can use the scan images to decide which parts of the prostate to take samples from.

- If your biopsy finds cancer, you probably won’t need another scan to check if it has spread, as the doctor can get this information from your first MRI scan. This means you can start talking about suitable treatments as soon as you get your biopsy results.

Disadvantages

- Being in the MRI machine can be unpleasant if you don’t like closed or small spaces. • Some men are given an injection of dye during the scan – this can sometimes cause mild side effects.

What does an MRI scan involve?

Before the scan the doctor or nurse will ask questions about your health. As the scan uses magnets, they will ask whether you have any implants that could be attracted to the magnet. For example, if you have a pacemaker for your heart you may not be able to have an MRI scan. You’ll also need to take off any jewellery or metal items.

You will lie very still on a table, which will move slowly into the scanner. MRI scanners are shaped like a doughnut or a long tunnel. If you don’t like closed or small spaces (claustrophobia), tell your radiographer (the person who takes the images).

The radiographer might give you an injection of a dye during the scan. The dye helps them see the prostate and other organs more clearly on the scan. It is usually safe, but can sometimes cause problems if you have kidney problems or asthma. So let the radiographer know if you have either of these, or if you know you’re allergic to the dye or have any other allergies.

The scan takes 30 to 40 minutes. The machine won’t touch you but it is very noisy and you might feel warm. The radiographer will leave the room but you’ll be able to speak to them through an intercom, and you might be able to listen to music through headphones.

Getting the results

Your MRI scan images will be looked at by a specialist called a radiologist, who specialises in diagnosing health problems using

X-rays and scans. The radiologist will give the images of your prostate a score from 1 to 5. You may hear this called your

PI-RADS (Prostate Imaging – Reporting and Data System) score or your Likert score. It tells your doctor how likely it is that you have cancer inside your prostate.

PI-RADS and Likert scores have the same values, and your score will be between 1 and 5.

• PIRADS or Likert score 1 It’s very unlikely that you have prostate cancer that needs to be treated.

• PIRADS or Likert score 2 It’s unlikely that you have prostate cancer that needs to be treated.

• PIRADS or Likert score 3 It isn’t possible to tell from the scan whether you have prostate cancer that needs to be treated – you may hear this called a borderline result.

• PIRADS or Likert score 4 It’s likely that you have prostate cancer that needs to be treated.

• PIRADS or Likert score 5 It’s very likely that you have prostate cancer that needs to be treated.

If your PI-RADS or Likert score is 1 or 2, this means you’re unlikely to have prostate cancer that needs to be treated. Your doctor may decide that you don’t need to have a biopsy.

They may suggest you have regular PSA tests so that any changes in your PSA level are picked up early. You’ll also be offered treatment for any urinary symptoms.

If your PI-RADS or Likert score is 3, your doctor will look at your other test results to help decide whether you should have a prostate biopsy to check for cancer. If they don’t think you need a biopsy, you’ll be offered regular PSA tests to check for any changes in your PSA level.

If your PI-RADS or Likert score is 4 or 5, you’ll usually be offered a prostate biopsy to find out whether you have cancer.

Scans to see if your cancer has spread

If you’re diagnosed with prostate cancer, you might need scans to find out the stage of your cancer – in other words, whether it has spread outside your prostate and how far it has spread. The results should help you and your doctor to discuss suitable treatments.

Your doctor or nurse can tell you what scans you might need to have. You might not need a scan if your PSA level is low and your previous results suggest that the cancer is unlikely to have spread.

MRI scan

An MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) scan uses magnets to create a detailed picture of your prostate and the surrounding tissues.

In many hospitals you may have a special type of MRI scan, called a multi-parametric MRI (mpMRI) scan, before having a biopsy. This can help your doctor see if there is any cancer inside your prostate, and how quickly any cancer is likely to grow. In other hospitals, you may have a biopsy first, followed by an MRI scan.

If you had an MRI scan before your biopsy that showed your cancer hasn’t spread outside the prostate, you may

not need another MRI scan. But if your doctor thinks your cancer may have spread, or if you didn’t have an MRI scan before your biopsy, you may have one. It will show whether the cancer has spread outside the prostate and where it has spread to. It will also help your doctor to work out the most suitable treatment options for you.

If you’ve recently had a biopsy, you may need to wait four to six weeks before you have an MRI scan. This is because the biopsy can cause bruising and bleeding around the prostate, which could affect the scan results.

Read our information on what MRI scans involve and what the results mean.

CT scan

A CT (computerised tomography) scan can show whether the cancer has spread outside the prostate, for example to the lymph nodes or nearby bones. Lymph nodes are part of your immune system and are found throughout your body. The lymph nodes near the prostate are a common place for prostate cancer to spread to. The scan results will help your doctor to work out the most suitable treatment options for you.

Your hospital might ask you not to eat or drink for a few hours before the scan. You’ll need to take off any jewellery or metal items, as these can affect the images.

At your scan appointment, you’ll be given a special dye to help the doctor see the prostate and other organs more clearly on the scan. It’s not radioactive. Most hospitals give you the dye as an injection. But some give the dye as a drink. The dye can give you a warm feeling and you might feel like you need to go to the toilet.

Before your scan appointment let your doctor know if you already know you are allergic to the dye, you have any other allergies, or you are taking the drug metformin for diabetes.

The CT scanner is shaped like a large doughnut. You will lie on a table that moves slowly through the hole in the middle of the scanner. The radiographer will leave the room but you’ll be able to speak to them through an intercom, and they can see you at all times. You will need to keep still, and you might be asked to hold your breath for short periods. The scan will take up to 20 minutes.

Bone scan

A bone scan can show whether any cancer cells have spread to your bones, which is a common place for prostate cancer to spread to.

Tell your doctor or nurse if you have arthritis or have ever had any broken bones or surgery to the bones, as these will also show up on the scan.

You might be asked to drink plenty of fluids before and after the scan. A small amount of dye is injected into a vein in your arm and travels around your body. If there is any cancer in the bones, the dye will collect in these areas and show up on the scan. It takes two to four hours for the dye to travel around your body and collect in your bones so you’ll need to wait a while before you have the scan.

You will lie on a table while the scanner moves very slowly down your body taking pictures. This takes around 30 minutes.

The doctor will look at the scan images to see if there is any cancer in your bones. Areas where the dye has collected may be cancer – these are sometimes called ‘hot spots’. You may need to have X-rays of any ‘hot spots’ to check if they are cancer. If it’s still not clear, you may need an MRI scan or, very occasionally, a bone biopsy.

The dye used for a bone scan is safe but it is radioactive. So you should try to avoid close contact with children and pregnant women for up to 24 hours after the scan. And make sure you flush straight away after using the toilet for 24 hours after the scan.

PET scan

At some hospitals, you may be offered a PET (positron emission tomography) scan. This is more commonly used to see if prostate cancer has come back after treatment, rather than when you are first diagnosed. A PET scan is often combined with a CT scan (PET-CT) to give even more detail about any prostate cancer inside the body. The scan can detect very small areas of cancer.

Your hospital might ask you not to eat or drink for a few hours before the scan. You should avoid vigorous activity for 24 hours before your appointment. Try to wear loose and comfortable clothing for the scan. You’ll need to take off any jewellery or metal items, as these can affect the images.

Before the scan, a small amount of radioactive dye is injected into your arm or hand. There are two main types of dye that can be used – choline and PSMA (prostate specific membrane antigen). You’ll need to sit for an hour – and avoid moving and speaking – while the dye travels around your body and is absorbed. This is because any movement can affect where the dye goes in your body.

You will then lie on a table that will move into the scanner, which is shaped like a large doughnut. The radiographer will leave the room but they can see you and speak to you. The scan usually takes up to 30 minutes. It won’t be painful but you may feel uncomfortable, as you need to lie still as the scanner takes pictures of your body.

The scanner works by detecting the radiation given off by the dye, which collects in areas that may be cancer.

You should be able to go home soon after the scan. You will be asked to avoid contact with children and pregnant women for a few hours after the scan, as you will be giving off a small amount of radiation during this time.

Drinking plenty of fluid after the scan can help flush the radiation from your body.

Getting my scan results

Your doctor or nurse will tell you how long it will take for the results of all the tests to come back. It’s usually around two weeks.

Your doctor will use your scan results to work out the stage of your cancer – in other words, how far it has spread.

This is usually recorded using the TNM (Tumour-Nodes-Metastases) system.

• The T stage shows how far the cancer has spread in and around the prostate.

• The N stage shows whether the cancer has spread to the lymph nodes.

• The M stage shows whether the cancer has spread (metastasised) to other parts of the body.

T stage

The T stage shows how far the cancer has spread in and around the prostate. A DRE or MRI scan is usually used to find out the T stage, and sometimes a CT scan.

T1 prostate cancer

The cancer can’t be felt during a DRE or seen on scans, and can only be seen by looking at your biopsysample under a microscope.

T2 prostate cancer

The cancer can be felt during a DRE or seen on scans, but is still contained inside the prostate. • T2a The cancer is in half of one side (lobe) of the prostate, or less.

• T2b The cancer is in more than half of one of the lobes, but not in both lobes of the prostate. • T2c The cancer is in both lobes but is still inside the prostate.

T3 prostate cancer

The cancer can be felt during a DRE or seen breaking through the outer layer (capsule) of the prostate.

• T3a The cancer has broken through the outer layer of the prostate, but has not spread to the seminal vesicles (which produce and store some of the fluid in semen).

• T3b The cancer has spread to the seminal vesicles.

T4 prostate cancer

The cancer has spread to nearby organs, such as the bladder, back passage or pelvic wall.

N stage

The N stage shows whether the cancer has spread to the lymph nodes near the prostate. Lymph nodes are part of your immune system and are found throughout your body. The lymph nodes near the prostate are a common place for prostate cancer to spread to.

An MRI scan or CT scan is used to find out your N stage.

The possible N stages are:

• NX The lymph nodes were not looked at, or the scans were unclear. • N0 No cancer can be seen in the lymph nodes.

• N1 The lymph nodes contain cancer.

If your scans suggest that your cancer has spread to the lymph nodes (N1), you will be diagnosed with either locally advanced or advanced prostate cancer. This will depend on whether the cancer has spread to other parts of the body.

M stage

The M stage shows whether the cancer has spread (metastasised) to other parts of the body, such as the bones. A bone scan is usually used to find out your M stage. Your doctor may offer you a bone scan if they think your cancer may have spread. You might not need a bone scan if the result is unlikely to affect your treatment options.

The possible M stages are:

• MX The spread of the cancer wasn’t looked at, or the scans were unclear. • M0 The cancer hasn’t spread to other parts of the body.

• M1 The cancer has spread to other parts of the body.

If you have a bone scan and it shows your cancer has spread to other parts of your body (M1), you will be diagnosed with advanced prostate cancer.

What do my scan results mean?

Your TNM stage is used to work out if your cancer is localised, locally advanced or advanced. This can help your doctor see how far it has spread and which treatment might be suitable for you.

Localised prostate cancer

Cancer that’s contained inside the prostate. Sometimes called early prostate cancer. Possible TNM stages are: • T stage: T1 or T2

• N stage: N0 or NX

• M stage: M0 or MX.

Locally advanced prostate cancer

Cancer that’s started to break out of the prostate, or has spread to the area just outside it. Possible TNM stages are: • T stage: T1 or T2

• N stage: N1

• M stage: M0

or

• T stage: T3 or T4 • N stage: N0 or N1 • M stage: M0.

Advanced prostate cancer

Cancer that’s spread from the prostate to other parts of the body. Also known as metastatic prostate cancer. Possible TNM stages are:

• T stage: any T stage

• N stage: any N stage

• M stage: M1.

What happens next?

Your doctor will look at your test results with a team of health professionals. You might hear this called your multi- disciplinary team (MDT). Based on your results, you and your doctor will talk about the next best step for you. Read our information for men who’ve been diagnosed with prostate cancer.

Prostate biopsy

What is a prostate biopsy?

A prostate biopsy involves using thin needles to take small samples of tissue from the prostate. The tissue is then looked at under a microscope to check for cancer. If cancer is found, the biopsy results will show how aggressive it is – in other words, how likely it is to spread outside the prostate.

There are two main types of prostate biopsy:

• trans-rectal ultrasound (TRUS) guided biopsy • transperineal biopsy.

Talk to your doctor or nurse about whether you will have a TRUS biopsy or a transperineal biopsy.

In many hospitals you may have a special type of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan, called a multi-parametric MRI (mpMRI) scan, before having a biopsy. In other hospitals you may have a biopsy first.

What are the advantages and disadvantages of having a biopsy?

Your doctor should talk to you about the advantages and disadvantages of having a biopsy. If you have any concerns, discuss them with your doctor or specialist nurse before you decide whether to have a biopsy.

Advantages

- It’s the only way to find out for certain if you have cancer inside your prostate. • It can help find out how aggressive any cancer might be – in other words, how likely it is to spread.

- It can pick up a faster growing cancer at an early stage, when treatment may prevent the cancer from spreading to other parts of the body.

- If you have prostate cancer, it can help your doctor or nurse decide which treatment options may be suitable for you.

- If you have prostate cancer, you’ll usually need to have had a biopsy if you want to join a clinical trial in the future. This is because the researchers may need to know what your cancer was like when it was first diagnosed.

Disadvantages

- The biopsy can only show whether there was cancer in the samples taken, so it’s possible that cancer might be missed.

- It can pick up a slow growing or non-aggressive cancer that might not cause any symptoms or problems in your lifetime. You’d then have to decide whether to have treatment or whether to have your cancer monitored. Treatment can cause side effects that can be hard to live with. But having your cancer monitored rather than having treatment might make you worry about your cancer.

- A biopsy has side effects and risks, including the risk of getting a serious infection.

- If you take medicines to thin your blood, you may need to stop taking them for a while, as the biopsy can cause some bleeding for a couple of weeks.

What does a prostate biopsy involve?

If you decide to have a biopsy, you’ll either be given an appointment to come back to the hospital at a later date or offered the biopsy straight away.

Before the biopsy you should tell your doctor or nurse if you’re taking any medicines, particularly antibiotics or medicines that thin the blood.

You may be given some antibiotics to take before your biopsy, either as tablets or an injection, to help prevent infection. You might also be given some antibiotic tablets to take at home after your biopsy. It’s important to take them all so that they work properly.

A doctor, nurse or radiologist will do the biopsy. There are two main types of biopsy: • a trans-rectal ultrasound (TRUS) guided biopsy, where the needle goes through the wall of the back passage • a transperineal biopsy, where the needle goes through the skin between the testicles and the back passage (the perineum).

What is a TRUS biopsy?

This is the most common type of biopsy in the UK. The doctor or nurse uses a thin needle to take small samples of tissue from the prostate.

You’ll lie on your side on an examination table, with your knees brought up towards your chest. The doctor or

nurse will put an ultrasound probe into your back passage (rectum), using a gel to make it more comfortable. The ultrasound probe scans the prostate and an image appears on a screen. The doctor or nurse uses this image to guide where they take the cells from. If you’ve had an MRI scan, the doctor or nurse may use the images to decide which areas of the prostate to take biopsy samples from.

You will have an injection of local anaesthetic to numb the area around your prostate and reduce any discomfort. The doctor or nurse then puts a needle next to the probe in your back passage and inserts it through the wall of the back passage into the prostate. They usually take 10 to 12 small pieces of tissue from different areas of the prostate. But, if the doctor is using the images from your MRI scan to guide the needle, they may take fewer samples.

The biopsy takes 5 to 10 minutes. After your biopsy, your doctor may ask you to wait until you’ve urinated before you go home. This is because the biopsy can cause the prostate to swell, so they’ll want to make sure you can urinate properly before you leave.

What is a transperineal biopsy?

This is where the doctor inserts the biopsy needle into the prostate through the skin between the testicles and the back passage (perineum). In the past, hospitals would only offer a transperineal biopsy if other health problems meant you couldn’t have a TRUS biopsy. But many hospitals have stopped doing TRUS biopsies and now only do transperineal biopsies.

A transperineal biopsy is normally done under general anaesthetic, so you will be asleep and won’t feel anything. A general anaesthetic can cause side effects – your doctor or nurse should explain these before you have your biopsy. Some hospitals now do transperineal biopsies using a local anaesthetic, which numbs the prostate and the area around it, or a spinal (epidural) anaesthetic, where you can’t feel anything in your lower body.

The doctor will put an ultrasound probe into your back passage, using a gel to make this easier. An image of the prostate will appear on a screen, which will help the doctor to guide the biopsy needle.

If you’ve had an MRI scan, the doctor may just take a few samples from the area of the prostate that looked unusual on the scan images. This is known as a targeted biopsy.

Or they might decide to take up to 25 samples from different areas of the prostate. You may hear this called

a template biopsy, as the doctor places a grid (template) over the area of skin between the testicles and back passage. They then insert the needle through the holes in the grid, into the prostate. A template biopsy is sometimes used if a TRUS biopsy hasn’t found any cancer, but the doctor still thinks there might be cancer.

A transperineal biopsy usually takes about 20 to 40 minutes. If you’ve had a general anaesthetic, you will need to wait a few hours to recover from the anaesthetic before going home. And you will need to get someone to take you home. Your doctor may ask you to wait until you’ve urinated. This is because the biopsy can cause the prostate to swell, so they’ll want to make sure you can urinate properly before you leave.

What are the side effects of a biopsy?

Having a biopsy can cause side effects. These will affect each man differently, and you may not get all of the possible side effects.

Pain or discomfort

Some men feel pain or discomfort in their back passage (rectum) for a few days after a TRUS biopsy. Others feel a dull ache along the underside of their penis or lower abdomen (stomach area). If you have a transperineal biopsy, you may get some bruising and discomfort in the area where the needle went in for a few days afterwards. If you receive anal sex, wait about two weeks, or until any pain or discomfort from your biopsy has settled, before having sex again. Ask your doctor or nurse at the hospital for further advice.

Some men find the biopsy painful, but others have only slight discomfort. Your nurse or doctor may suggest taking mild pain-relieving drugs, such as paracetamol, to help with any pain.

If you have any pain or discomfort that doesn’t go away, talk to your nurse or doctor.

Short-term bleeding

It’s normal to see a small amount of blood in your urine or bowel movements for about two weeks. You may also notice blood in your semen for a couple of months – it might look red or dark brown. This is normal and should get better by itself. If it takes longer to clear up, or gets worse, you should see a doctor straight away.

A small number of men (less than 1 in 100) who have a TRUS biopsy may have more serious bleeding in their urine or from their back passage (rectum). This can also happen if you have a transperineal biopsy but it isn’t very common. If you have severe bleeding or are passing lots of blood clots, this is not normal. Contact your doctor or nurse at the hospital straight away, or go to the accident and emergency (A&E) department at the hospital.

Infection

Some men get an infection after their biopsy. This is more likely after a TRUS biopsy than after a transperineal biopsy. It’s very important to take any antibiotics you’re given, as prescribed, to help prevent this. But you might still get an infection even if you take antibiotics.

Symptoms of a urine infection may include: • pain or a burning feeling when you urinate • dark or cloudy urine with a strong smell • needing to urinate more often than usual • pain in your lower abdomen (stomach area).

If you have any of these symptoms, contact your doctor or nurse at the hospital straight away. If you can’t get in touch with them, call your GP.

Around 3 in 100 men (three per cent) who have a TRUS biopsy get a more serious infection that requires going to hospital. If the infection spreads into your blood, it can be very serious. This is called sepsis. Symptoms of sepsis may include:

• a high temperature (fever)

• chills and shivering

• a fast heartbeat

• fast breathing

• confusion or changes in behaviour.

If you have symptoms of sepsis, go to your nearest hospital A&E department straight away.

Acute urine retention

A small number of men find they suddenly and painfully can’t urinate after a biopsy – this is called acute urine retention. This happens because the biopsy can cause the prostate to swell, making it difficult to urinate. Acute urine retention may be more likely if you have a template biopsy. This is because more samples are taken, so there may be more swelling.

Your doctor will make sure you can urinate before you go home after your biopsy. If you can’t urinate, you might need to have a catheter for a few days at home – this is a thin tube that’s passed into your bladder to drain urine out of the body.

If you develop acute urine retention at home, contact your doctor or nurse at the hospital straight away, or go to your nearest A&E department. You might need a catheter for a few days.

Sexual problems

You can masturbate and have sex after a biopsy. If you have blood in your semen, you might want to use a condom until the bleeding stops.

A small number of men have problems getting or keeping an erection (erectile dysfunction) after having a biopsy. This may happen if the nerves that control erections are damaged during the biopsy. It isn’t very common and it should get better over time, usually within two months. Speak to your doctor or nurse if you’re worried about this. What do my biopsy results mean?

The biopsy samples will be looked at under a microscope to check for any cancer cells. Your doctor will be sent a

report, called a pathology report, with the results. The results will show whether any cancer was found. They may also show how many biopsy samples contained cancer and how much cancer was present in each sample.

It can take up to two weeks to get the results of the biopsy. Ask your doctor or nurse when you’re likely to get the results. You might be sent a copy of the pathology report. And you can ask to see copies of letters between the hospital and your GP. If you have trouble understanding any of the information, ask your doctor to explain it.

If cancer is found

If cancer is found, this is likely to be a big shock, and you might not remember everything your doctor or nurse tells you. It can help to take a family member, partner or friend with you for support when you get the results. You could also ask them to make some notes during the appointment.

It could help to ask your doctor if you can record the appointment using your phone or another recording device. You have a right to record your appointment if you would like to because it’s your personal data. But let your doctor or nurse know if and why you are recording them as not everyone is comfortable being recorded.

How likely is my prostate cancer to spread?

Your biopsy results will show how aggressive the cancer is – in other words, how likely it is to spread outside the prostate. You might hear this called your Gleason grade, Gleason score, or grade group.

Gleason grade

When cells are seen under the microscope, they have different patterns, depending on how quickly they’re likely to grow. The pattern is given a grade from 1 to 5 – this is called the Gleason grade. Grades 1 and 2 are not included on pathology reports as they are similar to normal cells. If you have prostate cancer, you will have Gleason grades of 3, 4 and 5. The higher the grade, the more likely the cancer is to spread outside the prostate.

Gleason score

There may be more than one grade of cancer in the biopsy samples. An overall Gleason score is worked out by adding together two Gleason grades.

The first is the most common grade in all the samples. The second is the highest grade of what’s left. When these two grades are added together, the total is called the Gleason score.

Gleason score = the most common grade + the highest other grade in the samples

For example, if the biopsy samples show that:

• most of the cancer seen is grade 3, and

• the highest grade of any other cancer seen is grade 4, then • the Gleason score will be 7 (3+4).

If your Gleason score is made up of two of the same Gleason grades, such as 3+3, this means that no other Gleason grade was seen in the samples.

If you have prostate cancer, your Gleason score will be between 6 (3+3) and 10 (5+5).

Grade group

Your doctor might also talk about your “grade group”. This is a new system for showing how aggressive your prostate cancer is likely to be. Your grade group will be a number between 1 and 5 (see table).

What does the Gleason score or grade group mean?

The higher your Gleason score or grade group, the more aggressive the cancer and the more likely it is to grow and spread. We’ve explained the different Gleason scores and grade groups that can be given after a prostate biopsy below. This is just a guide. Your doctor or nurse will talk you through what your results mean.

Gleason score 6 (3 + 3) All of the cancer cells found in the biopsy look likely to grow very slowly, if at all (grade group 1).

Gleason score 7 (3 + 4) Most of the cancer cells found in the biopsy look likely to grow very slowly, if at all. There are some cancer cells that look likely to grow at a moderate rate (grade group 2).

Gleason score 7 (4 + 3) Most of the cancer cells found in the biopsy look likely to grow at a moderate rate. There are some cancer cells that look likely to grow slowly (grade group 3).

Gleason score 8 (3 + 5) Most of the cancer cells found in the biopsy look likely to grow slowly. There are some cancer cells that look likely to grow quickly (grade group 4).

Gleason score 8 (4 + 4) All of the cancer cells found in the biopsy look likely to grow at a moderate rate (grade group 4).

Gleason score 8 (5 + 3) Most of the cancer cells found in the biopsy look likely to grow quickly. There are some cancer cells that look likely to grow slowly (grade group 4).

Gleason score 9 (4 + 5) Most of the cancer cells found in the biopsy look likely to grow at a moderate rate. There are some cancer cells that are likely to grow quickly (grade group 5).

Gleason score 9 (5 + 4) Most of the cancer cells found in the biopsy look likely to grow quickly. There are some cancer cells that look likely to grow at a moderate rate (grade group 5).

Gleason score 10 (5 + 5) All of the cancer cells found in the biopsy look likely to grow quickly (grade group 5).

What type of prostate cancer do I have?

Your doctor will look at your biopsy results to see what type of prostate cancer you have. For most men who are diagnosed, the type of prostate cancer is called adenocarcinoma or acinar adenocarcinoma – you might see this written on your biopsy report. There are other types of prostate cancer that are very rare. Read more about rare prostate cancers.

If no cancer is found

If no cancer is found this is likely to be reassuring. However, this means ‘no cancer has been found’ rather than ‘there is no cancer’. Sometimes, there could be some cancer that was missed by the biopsy needle.

What else might the biopsy results show?

Sometimes a biopsy may find other changes to your prostate cells, called prostate intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN) or atypical small acinar proliferation (ASAP). Read more about PIN and ASAP.

What happens next?

If cancer is found

Your doctor or nurse will talk you through what your results mean. You might need scans to find out whether the cancer has spread outside the prostate and where it has spread to.

Your doctor will look at all of your test results with a team of health professionals. You might hear this called your multi-disciplinary team (MDT). Based on your results, you and your doctor will talk about the next best step for you. Read our information for men who’ve just been diagnosed.

If no cancer is found

Your doctor will look at your other test results and your risk of prostate cancer so that you can discuss what to do next.

If your doctor thinks you may have prostate cancer that hasn’t been found, they might suggest having another biopsy or an MRI scan.

If your doctor thinks you probably don’t have prostate cancer, they may offer to monitor your prostate with regular PSA tests to see if there are any changes in the future.

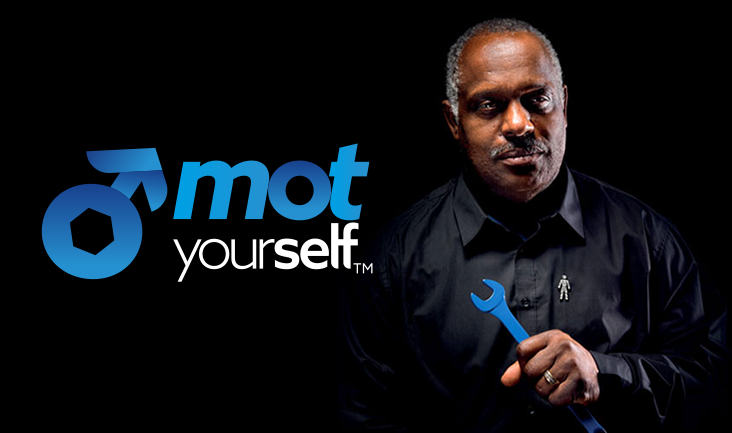

Get support

If you are concerned about prostate cancer or prostate problems we can help. We provide a range of information and support so you can choose the services that work for you. All our services are open to men, their family and their friends. Errol and his team at The Errol McKellar Foundation will be available to provide support.